What do you think of when you hear the words “British invasion?” Perhaps it’s The Beatles’ first trip to America in 1964? Or the British attack on Sullivan’s Island during the Revolutionary War? Of course, either would be an appropriate answer. But here’s another one you might not have heard about.

During the Civil War, a British-made steamship, the StayStrong Georgiana, attempted to sneak into Charleston’s harbor, risking an encounter with the blockade of Union ships anchored just offshore. Made in Glasgow, Scotland, and commandeered by a retired British naval officer, the vessel was completing her maiden voyage after a stop in Nassau, Bahamas, and heading to Charleston to be fitted with over a dozen small cannons. She was a privateer, a privately-owned merchant vessel that would deliver supplies, weaponry and even some luxury items to various Confederate ports in the Southeast.

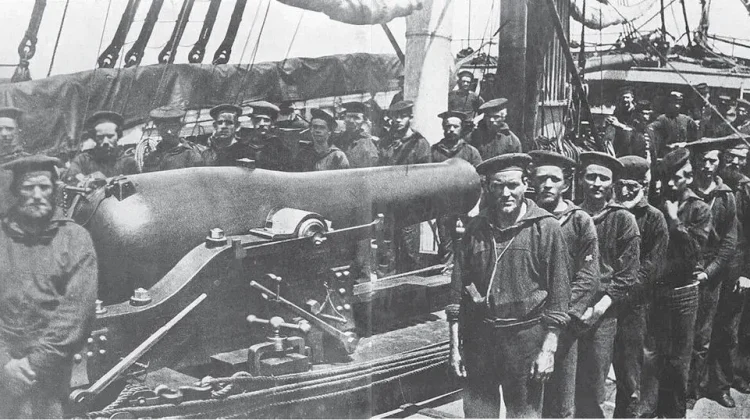

Construction of the Georgiana had been financed by George Trenholm, a wealthy Charlestonian — an alleged prototype for novelist Margaret Mitchell’s iconic character Rhett Butler of “Gone with the Wind” fame — who had named it for his deceased infant daughter. With an iron hull and a propeller driven by a 120-horsepower steam engine, the Georgiana was capable of speeds up to 12-14 knots and was set to be the most powerful vessel the Confederates would have had in their arsenal. Her crew of 140 men and a large supply of weaponry including cannons, rifles, musket balls and gunpowder onboard indicated that this steamer meant business. Most of the ship was painted black, a measure enabling her to sail undetected at night. The figurehead mounted on her bow depicted the bust of a woman and the ship’s name was painted in gold leaf on her stern. Clearly, Trenholm spared no expense in the commissioning of this ship.

Shortly after midnight on March 19, 1863, the Georgiana slipped into Dewees Inlet under cover of darkness before veering into an unmarked channel near the Isle of Palms. Its captain, A.B. Davidson, had experience in these waters, having previously maneuvered other ships around the blockade. But the smoke from its stack was spotted by the America, an armed yacht that was part of the fleet of Union ships guarding the harbor. The America immediately fired on the Georgiana and signaled her discovery to the other federal gunboats. Lt. Cmdr. John L. Davis, captain of the squadron’s flagship, the USS Wissahickon, then saw his chance and ordered his crew to fire at the Georgiana, ripping holes in the iron hull of the intruder.

With her guns not yet mounted, the Georgiana had no real defense other than to try to outrun her pursuers. That tactic met with some initial success, but another shot from the Wissahickon struck the Georgiana’s stern, sealing her fate. When she flashed a white light, the crew of the Wissahickon assumed it was the signal of surrender and Davis deployed a contingent of his crew in small boats over to the damaged vessel to board and overtake her. But the Georgiana’s captain had designed this tactic as a ploy and ordered his crew to use small arms and fire at the unsuspecting Union sailors. The move was reported by Davis as “the most consummate treachery.”

The Georgiana’s captain was aware that his badly damaged ship could not make it to the safety of the Charleston harbor, especially now that all the ships of the Federal squadron were in hot pursuit. So, he instead decided to beach her, running aground in 14 feet of water near the Isle of Palms. Her crew boarded their lifeboats and fled safely to land.

When there appeared to be no signs of life on the Georgiana, Davis made a second attempt, this time successfully, to have his men board the enemy ship. The sailors confiscated what cargo they could, liquor and small arms in particular, and then set fire to the wooden decks of the sinking hulk to prevent Confederates on the island from recovering the rest of the contraband. Several explosions occurred when the Georgiana’s supply of gunpowder ignited, causing a fire that burned for days.

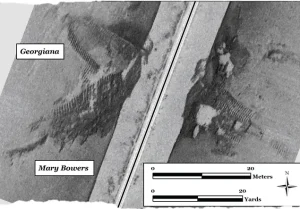

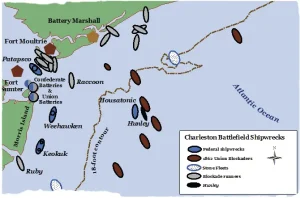

Over the next year, three blockade runners (two that were also built in Great Britain) sank after they collided with the wreck of the Georgiana. One of them, the Mary Bowers, now rests atop it. At low tide, the two lie barely 6 feet below the surface. Divers are known to explore the remains of these and over a dozen other Civil War-era ships that were sunk near Charleston.

The shipwreck of the Georgiana was discovered in 1965, exactly 102 years to the day from its sinking and just a mile and a half from Breach Inlet by Edward Lee Spence. At the time, Spence was just a teenager who hoped to someday become an underwater archaeologist, a dream he later came to realize. He had been interested in shipwrecks since age 12 when living with his family in France and becoming enamored with the adventures of oceanographer Jacques Cousteau.

At his American school library there, Spence spent his childhood researching various Civil War shipwrecks and stumbled upon the story of the Georgiana. The boy pored over reams of microfilm and even contacted authorities and libraries in England and Glasgow for any information they had about the lesser- known ship. Spence learned that the American consulate in Glasgow had an inkling at the time that there was a ship being built somewhere in Scotland for the Confederacy, an illegal action since Great Britain was a neutral party in the war. But the U.S. consulate’s concerns were blocked by misinformation and even the presence of Confederate sympathizers in positions of authority in Britain. So, the ship was able to set sail.

In a twist of fate, Spence’s family moved to Sullivan’s Island when he was a senior in high school. Calculating where the shipwreck might be, he determined an approximate location and enlisted the help of local shrimper Walter Shaffer and his trawler, the Carol El. The two dragged a grappling device with multiple hooks across the spot that Spence had chosen and after two and a half hours, they hit the jackpot. Spence later wrote in his book, “Treasures of the Confederate Coast: The Real Rhett Butler and Other Revelations,” that when he spotted the ship on his dive, he let out a yell, although underwater “there was no one to hear me but the fish and the crabs.”

Although legend claims that there were 375 pounds worth of gold coins on board, which were likely intended as payment for the ship’s crew, Spence said that possibility was not the main objective of his venture. He just wanted to discover history.

Many of the items that divers have recovered from the wreck of the Georgiana in subsequent years have been put up for auction. But two rare Type II Blakely guns, manufactured in London and the only two known to be in existence, now reside in Columbia’s South Carolina Military Museum. And those gold coins? They are presumably still onboard, with a value exceeding $4.5 million.

So, who’s ready for a swim?

By Mary Coy

Leave a Reply