Two Lowcountry residents are dead after attempting to swim the treacherous waters of Breach Inlet on May 6. An 18-year-old woman, Yoselin Lopez-Perez, and a 28-year-old man, Guillermo Quintero-Camacho from the Charleston area, were unresponsive after first responders from both Isle of Palms and Sullivan’s Island police and fire departments pulled them from the water and performed lifesaving procedures, following 911 calls from local witnesses saying that two swimmers were in distress.

EMS workers raced Lopez-Perez to East Cooper Medical Center, but she was pronounced dead from drowning shortly after arrival. Quintero-Camacho was taken to MUSC Trauma Center, where, despite hanging on, he remained unresponsive and was pronounced dead from drowning early the next morning.

“Isle of Palms Police is the investigating agency for this case and we are working with the Charleston County Coroner’s Office,” said Sgt. Matt Storen, special services and public information officer with IOPPD.

Sullivan’s Island Fire Chief Anthony Stith speculated that Quintero-Camacho might have gone in to save Lopez-Perez and got into the same trouble, as both were 20 to 30 feet off the beach in water in which the depth is constant shifting.

“Two calls came in from witnesses saying they could see the male bobbing up and down as if he were holding onto something,” Stith said. “They went in on the Isle of Palms side and we were just not lucky that they didn’t survive.”

Both Stith and Storen, however, pointed out that the inlet, which separates Isle of Palms from Sullivan’s Island, has long been a ready-made death trap for all would-be swimmers.

“I’ve been here 43 years and Breach Inlet currents are always running under the water,” Stith said. “They are very strong – and some of the currents run at 30 knots (approximately 34 mph) which is very fast. It’s a terrible place that often looks calm.”

Whether the waters are calm or rough, Storen reminds everyone that swimming in Breach Inlet is not only dangerous, but also unlawful. “There is no swimming allowed at Breach Inlet,” he said. “A city ordinance prohibits it.”

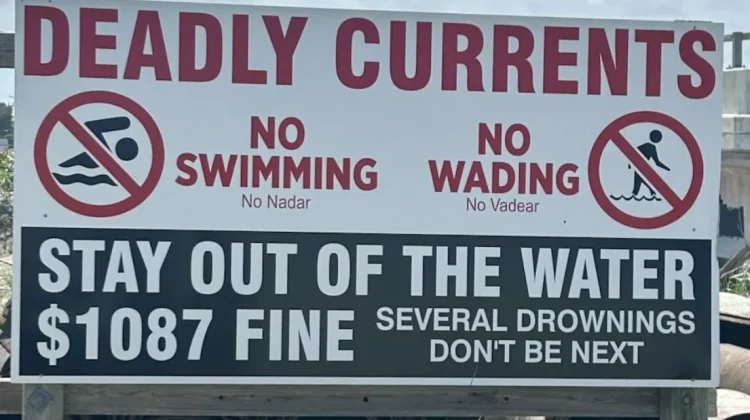

Area beach signs warn of “Deadly Currents – No Swimming – No Wading – Stay Out of the Water – Several Drownings – Don’t Be Next.”

If caught in the water, violators in IOPPD’s jurisdiction can be fined $1,087. For Sullivan’s Island, the fine is $1,040.

Stith added that part of the reason people violate this law is because they either don’t see the signs, can’t read the signs in English or just simply ignore the warnings because Breach Inlet on any given day looks like an inviting body of channel water, especially as you come across the

Palm Boulevard bridge and see the inlet up close. “But looks can be deceiving,” Stith said. “This is a very dangerous place to be in the water… And the warning signs are in Spanish now.”

Breach Inlet’s dangerous reputation goes back centuries to when these treacherous currents foiled battle plans. In a failed attempt to capture Fort Sullivan during the Revolutionary War in 1776, British generals realized that crossing the inlet would be risky, especially considering that the inlet at the time was a mile wide. But they still sent hundreds of men in 15 armed flatboats across the inlet supported by warships, artillery and infantry – all of which came to nothing as the American forces and the currents combined to defeat them.

One of the area’s historical markers even reads: “The shore and sandbars change constantly, as strong and dangerous tidal currents flow into and out of the salt marsh between the islands and the mainland.”

The Sullivan’s Island side of the inlet also recently underwent a long beach restoration project along 4,100 linear feet of shoreline, which added 76,000 cubic yards of sand (enough to fill 23 Olympic-size swimming pools) to the dunes, all of which made the area even more dangerous than usual.

Steven Traynum, IOP coastal engineer consultant and president of Coastal Science & Engineering in Columbia, said that as dangerous as it is to swim in the inlet, even just standing in shallow water is a coin flip for personal safety.

“I have surveyed the area before while standing in the inlet’s shallow water,” Traynum said. “There are natural changes of shoals moving around that area, with millions of cubic yards of shifting sand – such that the bottom topography changes very quickly – and makes negotiating the water tough even when you’re just standing in a few feet at low tide.”

“I have surveyed the area before while standing in the inlet’s shallow water,” Traynum said. “There are natural changes of shoals moving around that area, with millions of cubic yards of shifting sand – such that the bottom topography changes very quickly – and makes negotiating the water tough even when you’re just standing in a few feet at low tide.”

While the inlet can be a great spot for fishing, photography and dolphin sightings, both Stith and Storen urge everyone to heed the signs and warnings and the area’s history and to please think twice before taking a chance on becoming another unnecessary island casualty.

“I’m sorry these two people died,” Stith said. “But I hope in the future this kind of tragedy won’t happen anymore.”

By L. C. Leach III

Leave a Reply