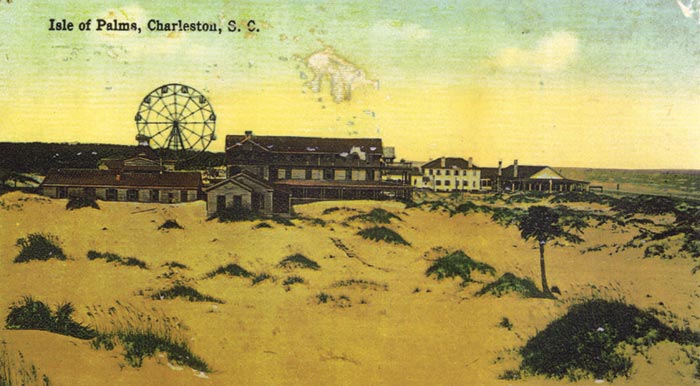

It’s a natural phenomenon that takes place along almost every shore and on every beach – but for decades people have tried everything to stop or at least slow the process of erosion. It’s an ongoing process Isle of Palms works tirelessly to manage, and the city and has made tremendous headway over the last 10 years.

City Administrator Linda Tucker said IOP has been very proactive and works hard to maintain a healthy beach.

“There had been minor projects done on the beach after Hurricane Hugo, but, until the last 10 years or so, there was not the careful monitoring or the local comprehensive beach management plan we have now.”

At one time, IOP had a beach patrol actively walking and monitoring the beach, but, as far as getting into the “science of managing the beach, that really didn’t begin until 2007,” Tucker explained.

“We’re now very involved in watching the entire shoreline, basically surveying it so we have the knowledge to know what’s happening and making sure we have ordinances in place to protect it,” she added.

Tucker said the island has experienced many shoal management events. There are two unstable inlet zones – the Dewees Inlet end and the Breach Inlet end – which are not uncommon on islands like Isle of Palms.

“They often change because of periodic shoal attachment,” she said. “The sand builds up offshore on the northeast end of the island, and that buildup moves close to the shoreline and eventually attaches to it, spreading laterally along the coast. It’s the beach naturally renourishing itself.”

There can be complications during this natural process, which has prompted city officials to do all they can to keep the beach healthy and at an even width.

“We do this to have a dry sand beach everywhere,” Tucker said. “With the help of citizens and the resources that give us assistance like FEMA, the state and private stakeholders, the city’s efforts are to keep a dry sand beach for the full seven miles of the island.”

Fortunately, Isle of Palms has a gently sloping shoreline.

“Many beaches have a huge drop-off, but IOP doesn’t have that,” Tucker said. “However, on either side of these shoal attachment processes, which happen about every seven years, we will get periodic erosion, and those are the times we step in to help even out the shoreline.”

When dredging is required to bring sand in from offshore, areas are monitored and tested to determine if they are good areas from which to borrow

“When harvesting sand, core samples must be taken to make sure the material brought in is right for the beach,” Tucker said. “You would think it’s all sand out there, but there’s rock, clay and high/low shell content, so we have to look at samples first.”

If sand that’s brought in is not compatible, it won’t last as long and could produce a negative environmental impact.

Tucker recalled that during the big restoration project in 2008, a cannonball was brought up early in the dredging process.

“They had to clear the area and call in the bomb squad, but it was determined to be solid and not dangerous,” she said.

The cannonball was initially sent to Fort Moultrie, where it was held until the city could get it preserved. It’s now on display at the IOP Recreation Center.

“It was an exciting thing to happen during that time, and, now, on the current restoration, we’ve learned that a portion of one of the areas surveyed to borrow from is a resting place for the Second Stone Fleet,” Tucker said.

She explained that these were whaling vessels that were filled with stone and sunk offshore in 1862, hoping to prevent Union blockade runners from entering Charleston Harbor.

With the potential of disrupting a proposed historic district, the borrow areas had to be moved outside of that area to find suitable sand.

“There wouldn’t be parts of the ships left at this point, of course,” Tucker said, “but there might be stone.”

Beach restoration will be an ongoing process for Isle of Palms.

“The science is ever evolving. We have so much more data now than we had years ago as to what’s happening out on the beach,” she said. “While it’s something all islands must pay attention to, we don’t really know what the evolution of inventions and new sciences may be in another 10 or 15 years, which may allow for different methods to try to manage this.”

Tucker said perhaps more natural methods will eventually be available to harvest offshore.

“I think we all look forward to the day we can figure out how to assist mother nature without interfering with it,” she said.

A couple of years ago, South Carolina beach communities got together and created an organization called South Carolina Beach Advocates.

“We all have similar problems that we deal with taking care of our shores,” Tucker said. “It’s more than just beach restoration. It means making sure they stay clean and safe.”

Only in its infancy, the organization gives a voice to the beach communities in the state.

“A big component of it was education and advocacy in taking care of our beaches,” Tucker explained. “I believe the group is becoming very effective at being a good repository of information and helping to educate people about why we need to do what’s necessary to take care of our shoreline.”

Tucker added that as a community, the issue of beach restoration can’t be ignored.

“Unmanaged erosion is not good for anyone who lives or visits here, and it’s not good for the habitat. We are stewards of our beach. It belongs to everyone and it’s important that we take care of it,” she concluded.

By Diane Pauldine

Leave a Reply