Editor’s Note: The following harrowing tale originally appeared in Hurricane Hugo – The Storm of the Century. For more survival tales about this powerful 1989 storm, visit the digital version of the magazine at www.HugoMagazine.com.

I would like to have been somewhere where I could have seen it,” said a Lowcountry resident who lost everything to Hugo.

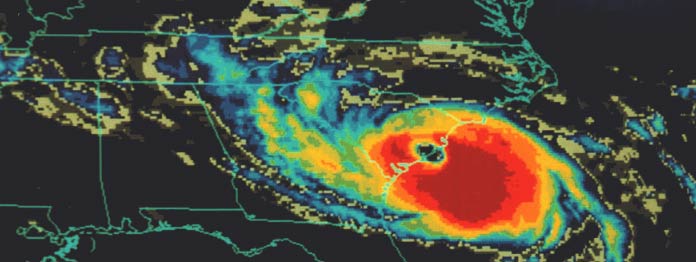

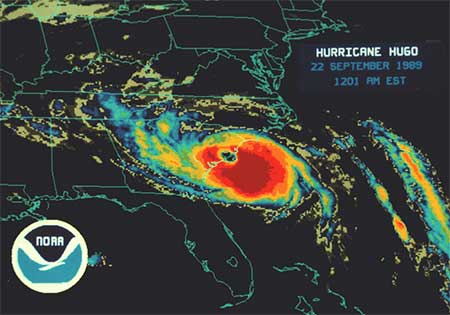

It’s a reaction shared by many. As the fiercest storm in modern history made landfall on the Isle of Palms, two young Medical University of South Carolina students were there and lived to tell about it.

The point in time most vivid to Michael A. Pulliam was acceptance of the belief that he would die. He and friend Kevin Williams were swept from the second floor of a house on front beach and were propelled through 12-foot white water currents for a city block, landing on the roof of a onestory house. Sense of time was suspended, he said; the water, the wind and ink-black darkness were his only perceptions.

Their experience with Hugo began calmly on Wednesday night as the two headed for the island to board up Pulliam’s family beach house at 2910 Palm Blvd. The young men went with the intention of remaining there during the hurricane.

“It was half crazy, I guess,” Pulliam said. “But I really like the outdoors in bad weather. We didn’t want it (Hugo) to hit, but we were excited about the onslaught.”

With no radio and a television that didn’t work, they were unaware that by 6 p.m. on Thursday, the storm was upgraded to Category 4, with winds of 135 mph predicted.

“We weren’t concerned at first,” Pulliam said, “because the winds were only 70 to 80 mph. But we had no television. If we had known the storm was upgraded, we’d have left.”

The two were in touch by phone with parents and friends in Columbia. Pulliam’s mother called the Isle of Palms Police Department to report the presence of the two on the island, Pulliam said. His grandfather called to instruct them to leave the two-story brick house, and go to the house next door, which was on stilts: “My grandfather was worried about the 12- to 18-foot tidal surge predicted. He didn’t think the house would stand. There was nowhere for the water to go.”

They left at 8:30, when the power went out.

“We gathered the candles and went next door,” to the house owned by Othniel Wienges of St. Matthews. “It was very, very dark.”

By 9 p.m., Hugo began to flex its muscles.

“The house started to shake and glass began to break upstairs,” said Pulliam.

They found a weather radio and learned that, incredibly, the storm was not predicted to make landfall for another three hours: “We realized then we were in for quite a ride.”

In the hours to come, said Pulliam, “the water became the most terrifying thing of all.” In less than an hour, the water had risen by 15 feet to seep into air conditioning ducts in their second-floor refuge. The floor’s linoleum would later become “a giant bubble, with water underneath.” Waves battered the structure.

The noise of the water and wind was not the only sensory input affecting Pulliam and Williams. As the eye approached, barometric pressures plummeted, causing ears to “pop” in a manner similar to ascending in an airplane.

A five-gallon water cooler in the house began to bubble. The strange calm of the hurricane’s eye lasted about 30 to 40 minutes.

“The wind slowed and it got quieter,” Pulliam said. “All you could hear was water under the house. We realized we’d both lost our cars (which were floating out front), but that didn’t bother us. We thought we were lucky to be alive.”

They also believed the worst was over.

“I thought, well, the house made it through the first part of the storm, and the second part can’t be as bad.”

As anyone who experienced the storm, even hundreds of miles inland, discovered, this was not the case.

“In the first part of the storm, the wind came from the front of the house,” said Pulliam, “and blew the water from the house. When the wind changed direction, it blew the water toward the house. The house started shaking and water started coming in through the sliding glass door. There were serious prayers going on in the kitchen.”

He recalled that the darkness was overwhelming: “I looked out the window. The houses are only 20 feet apart, but I couldn’t see my house. I thought it was gone.”

The young men realized a critical decision was in order. Should they risk a retreat to the volatile third floor or take their chances with the tides on the second floor?

“I went to the front door and opened it to see how high the water was,” Pulliam said. With Williams holding onto his shoulder, “I stuck a foot out the door. The wind sucked us out and the porch collapsed. It was like white water rapids. You don’t sink in water like that; you’re just carried along.”

Pulliam didn’t recall how long they lay face down on the roof of the one-story house a block away – maybe an hour he said. At approximately 3 a.m. “you could start to barely see again, and then the water went out as fast as it went in.”

As dawn broke at the still-standing Pulliam house, Michael recalled the scene of destruction: “There was a piano and furniture in the front yard which I thought at first was ours. There were appliances on the beach. It was like there was no civilization and you were alone. It was hard to imagine the peninsula was still there and functioning.”

When Hugo made landfall on the Isle of Palms, the two young men felt the storm in life-threatening dimensions but did not understand the full reach of its power. Hugo hit in the darkness of night, and sight was useless. Understanding, if it came at all, would not begin until morning.

Leave a Reply